Introduction

Here’s the thing, good barbecue is not luck, it is applied knowledge. In the first hundred words you need to see the core idea, so here it is. Cookout BBQ science depends on BBQ chemistry, the Maillard reaction in BBQ, heat transfer in cooking, smoke flavor compounds, and barbecue temperature control. If you understand those pieces you gain control over crust, tenderness, and aroma. This article shows practical steps, backed by plain chemistry, so you can stop guessing and start making consistent flavor.

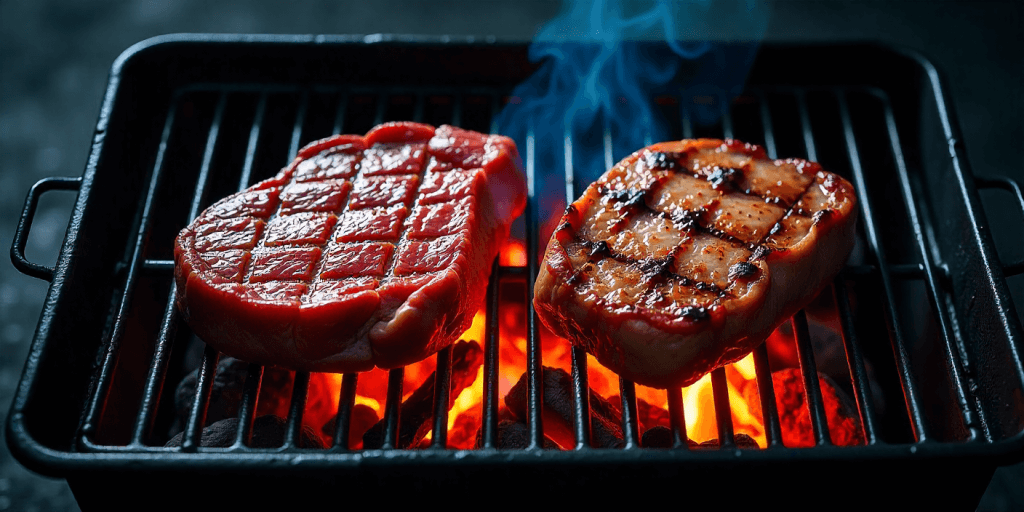

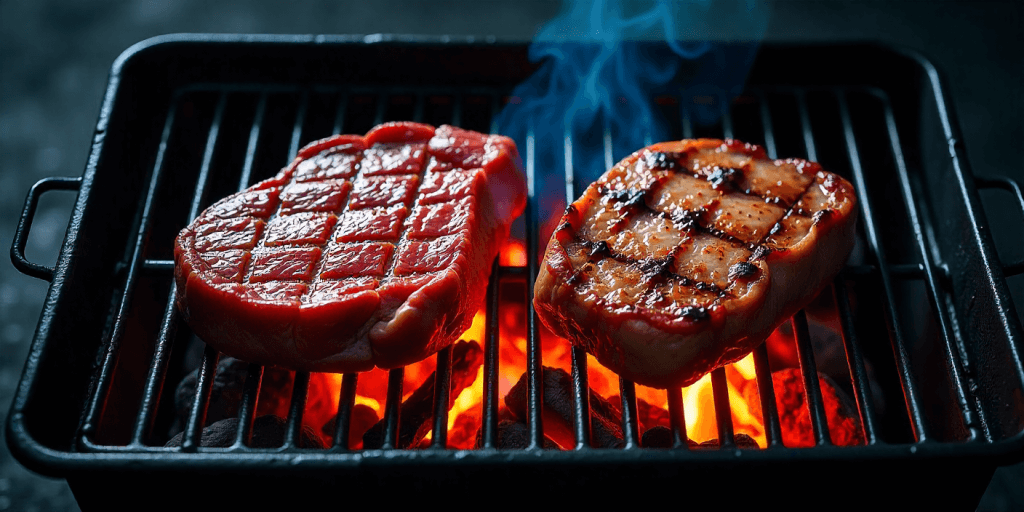

The Maillard Reaction, Why Sear Makes Flavor

Here’s the thing, the Maillard reaction is flavor engineering. When amino acids meet reducing sugars at high heat, dozens of volatile compounds form. Those compounds deliver roasted, nutty, and savory notes we call crust, bark, or sear. If you want to taste depth, you want these reactions, not char.

What this really means is you must manage surface moisture and temperature. Dry the surface, get the grill hot, and sear quickly to create the crust. Avoid continuous intense flame that burns rather than browns. Let that crust form, then move the cut to gentler heat so the interior finishes without drying out.

How Sugars and Amino Acids Create That Crust

Let’s break it down, sugars and amino acids are the raw materials. Under heat they rearrange and polymerize into brown pigments and aroma molecules. The more complex the sugar and amino acid mix, the richer the aroma palette becomes.

Here’s a practical tip. Lightly sugar in rubs helps browning but too much sugar burns. Balance sugar with salt and spices to guide the chemistry toward caramelization and Maillard products, not bitter carbon.

Heat Transfer and Grill Types, Charcoal, Gas, Pellet

Here’s the thing, grills do not all heat the same. Charcoal vs gas grilling changes how energy reaches the meat. Charcoal gives stronger radiant heat and variable convection, gas delivers steady convective heat, and pellet grills automate heat while adding wood smoke dynamics.

What this really means is choose the tool for the job. Use direct, hot charcoal for quick sears. Use gas when you need consistent midrange temps. Use pellets when you want long cooks with repeatable temperature control. Understand hot and cool zones on every grill and move the meat between them for best results.

Direct vs Indirect Heat, When to Use Each

Use direct heat when you want a fast crust on thin cuts, and use indirect heat when you need slow collagen breakdown in thicker pieces. Direct heat gives that immediate Maillard reaction, indirect heat lets interior chemistry catch up without overcooking the outside.

Practice a move called sear then rest. Sear over direct flame, then finish over indirect heat. That method keeps juices locked and develops flavor without resorting to guesswork.

Smoke Chemistry, Wood Species and Flavor Compounds

Here’s the thing, smoke is a cocktail of chemical compounds. Burning wood crops wood smoke flavor fragments, including hydroxybenzenes, aldehydes, and ketones. Those compounds follow to surface proteins and fats, giving that unmistakable smoky fragrance.

What this really means is different woods give different notes. Apple and cherry add sweet fruitiness, oak gives steady balance, and bolder woods produce assertive smoke. Match wood intensity to cut and seasoning so smoke complements rather than overwhelms.

Which Woods Pair Best With Which Meats

Match wood to the protein’s natural flavor profile and fat content. Lighter woods suit delicate flesh and give subtle fruity notes, while heavier woods pair with robust, fatty pieces. If you are not sure, test small pieces first and score taste across tribunals to learn what your palate prefers.

Remember, more smoke is not always the best. Aim for thin blue smoke, and avoid long fumes of white smoke that signal incomplete combustion and can taste bitter.

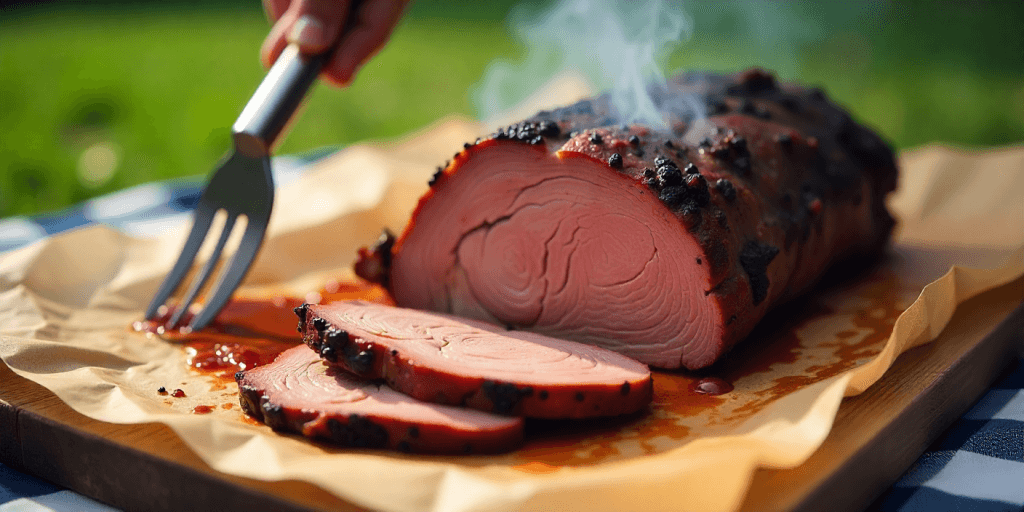

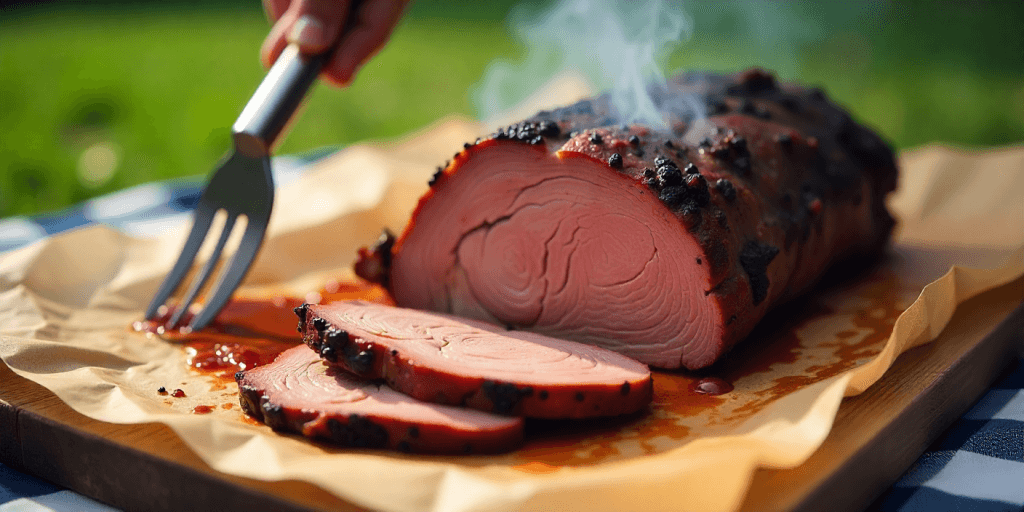

Meat Structure and Tenderization, Collagen, Enzymes, and Rest

Here’s the thing, muscle is muscle, but connective tissue makes or breaks texture. Collagen is a glue that tightens with heat then slowly breaks down into gelatin, which yields pull apart tenderness. Enzymes working postmortem also soften fibers early on, so aging matters.

What this really means is time and temperature pairing. For tough muscles you want slow, sustained heat so collagen has time to convert. For quick cooks, you lean on method and cuts that have less connective tissue. Rest after cooking lets cookout juices reallocate and proteins relax, which improves bite and mouthfeel.

Why Resting Meat Matters

Resting is not passive, it is finishing chemistry. During rest, residual heat stays reactions and muscle threads relax so liquid moves back into the meat as an alternative of paddling on the cutting board. For large pieces rest 20 to 45 minutes; for minor cuts 5 to 10 minutes is usually enough.

If you skip resting you risk losing moisture and clarity of flavor. Simple tents of foil are fine, avoid fully sealing because trapped steam softens crusts.

Temperature Control and Thermometers, Safe and Juicy Targets

Here’s the thing, internal temperature is the single best data point in a cook. Use calibrated probes to track internal temperature trends and the ambient pit temperature. Temperatures tell you when collagen has softened, when fat has properly rendered, and when food is safe.

What this really means is rely on numbers not clocks. Aim for known ranges for each cut, watch the stall where internal temp plateaus, and account for carryover rise so you pull at the right moment. Calibrate probes regularly and place them into the thickest muscle, away from bone and heavy fat pockets.

Where to Insert the Thermometer Probe

Proper placement avoids false readings. For irregular shapes take two readings, one in the thickest area and one where point meets flat. Read trends, not single spikes. If the reading jumps or drops unexpectedly, reposition the probe and let the next trend guide you.

Good placement beats guesswork every time.

Rubs, Marinades, and Brines, How Salt and Acid Transform Meat

Here’s the thing, flavors start before the grill. BBQ rubs and marinades layer in aromatics and structure. Salt in brines or rubs moves into muscle through brine osmosis and salt diffusion, altering proteins so they hold more water and taste seasoned.

What this really means is use brines for big pieces that need moisture retention. Use rubs for bold surface flavor and bark development. Use acid sparingly in marinades because too much softens proteins into an undesirable texture. Balance time and concentration to match cut thickness.

Salt, Time, and the Mechanics of Brining

Brining is straightforward science. Salt dissolves into tissue, changes the water-binding capacity, and modifies protein structure so juices stay inside during cooking. For quick brines use a common 5 to 8 percent salt solution by weight. For longer cures lower the concentration and increase time.

Rinse lightly and dry the surface before cooking to avoid over-salted crust and to allow a dry surface for better Maillard reaction performance.

Fire Management and Smoke Control, Airflow, Fuel Choices

Here’s the thing, air controls fire. Vent adjustments change combustion, and combustion changes smoke quality. Fire management in BBQ is tiny, precise corrections, not large swings. Learn how your vents respond and nudge them slowly.

What this really means is choose fuel and vent settings that suit the length of the cook. Lump charcoal offers quick, hot burns. Briquettes give steadier heat for long runs. Add wood chunks for controlled smoke, and always watch smoke color for clues—thin blue smoke is a good sign, thick white smoke is not.

When Smoke Becomes a Problem

Acrid smoke comes from poor combustion or wet fuel. That smoke leaves bitter residues and ruins the subtleties you worked for. The fix is simple. Add oxygen, raise the fire, or swap fuel. Avoid heavy sugar loads late in long smokes, they burn and taste off.

Common BBQ Myths vs Science, What Actually Works

Here’s the thing, many old rules are ritual, not fact. The “sear locks in juices” idea is a good story but not accurate. Juices escape when proteins contract, which happens no matter how many flips you do. A smoke ring does not mean deep smoke penetration, it signals a chemical reaction with myoglobin near the surface.

What this really means is run controlled tests. Try two identical pieces with single variable differences, like wood type or brine, then compare. Practical experiments deliver reliable upgrades faster than folklore.

Practical Checklist and Experiments for Your Next Cookout

Bring a probe thermometer and fresh batteries. Prep a hot zone for searing and a cooler zone for finishing. Keep a tasting notebook to record wood, rub, and time. Run one small experiment per cook, change one variable, and score results for tenderness, aroma, and crust.

Simple experiments you can run include wood pairing trials, brine versus rub comparatives, and reverse sear versus direct sear tests. Score each on a simple 1 to 10 rubric and repeat to confirm.

Case Study, Applewood Versus Oak on a Slow Shoulder

A home cook tried apple wood against oak using two adjacent but identical pieces. Everything else stayed the same, from rub to pit temp. The apple run produced a sweeter, more subtle smoke note that highlighted the rub. The oak run offered a sturdier, more pronounced smoke backbone that stood up to strong seasoning.

The cook noted apple scored higher for family dinners, oak scored higher for bold, sauced plates. Both validated a point. Wood matters, but match your smoke to the meal.

FAQs

Q1. What is Cookout BBQ science in plain words

A1. Cookout BBQ science explains how heat, smoke, and chemistry change meat into flavorful food.

Q2. Why does searing improve taste

A2. Searing triggers the Maillard reaction in BBQ, which forms complex aroma compounds on the surface.

Q3. How do I control smoke flavor

A3. Choose wood species, keep fuel dry, and manage airflow so you get thin blue smoke not dense white clouds.

Q4. When is meat done and still juicy

A4. Use internal temperature as your guide, account for carryover, and rest the cut to let juices redistribute.

Q5. Should I brine or rub for flavor

A5. Brine for moisture and even seasoning in thick pieces, rub for bold surface flavor and crust.

Conclusion

Here’s the thing, learning Cookout BBQ science converts guesswork into repeatable skill. Understand BBQ chemistry, tweak heat and smoke, and run small controlled tests. Over a few weekends you will build a public library of consistent cooks that taste the way you want. Practice, record, and refine, and you will stop hoping for good results and start making them.